I’ve been desperate to share my general excitement about this project since something like March of this year when we pretty much had the general concept settled.

It’s one of two pieces of work that’s had me endeavouring (and failing) to learn the art of patience in 2016 so I’m so thrilled we can now unveil our plans for the agroforestry field.

If you don’t want to read a long blog then the summary is:

We’re fully embracing experimenting with land use and will be delivering agroforestry in a way we don’t believe has been done in the UK before, through a multi-tiered arrangement of land owner (The Dartington Hall Trust), farm tenant (Jon and Lynne Perkin, Dartington Dairy at Old Parsonage Farm) and agroforestry tree license holders.

What makes this unusual – and exciting – is that by enabling several different businesses to work together in farming the field (the license holders and the tenant farmer) we’ve created an approach to agroforestry that overcomes some of the traditional barriers which have prevented a wider uptake of agroforestry in the UK.

Jon and Lynne are setting up a dairy business in the South West in the current economic climate, they can’t afford to plant thousands of trees which will require years of maintenance before a return on investment and they’re livestock farmers not arborists. In this model they will continue managing the rows between trees as part of their 7 year silage/arable rotation and will be financially compensated for the area lost to the tree rows by the licences. The investment in the trees will be made by separate businesses, which have a market incentive to invest in tree crops to meet the demands for their products and which specialise in the tree crops being grown but do not have the land available to the Perkins.

In our case, the license holders include Luscombe Drinks, a local soft drinks producer who will be growing 1,600 elderflower trees to help meet the increasing demand for their Elderflower Bubbly.

The Apricot Centre at Huxhams Cross Farm, a community owned biodynamic farm based on the estate and run by expert top fruit grower Marina O’Connell, will join them. They will be planting 600 edible and juicing apples. Apple varieties include Discovery, Saturn, Fiesta, Ashmeads kernel, Rajka, Egremont Russet and Monarch.

Lastly The Dartington Hall Trust itself, in partnership with Salthouse & Peppermongers, will be growing the UK’s first ever commercial table crop of sichuan pepper, starting with 150 trees (well 96 in 2016 but 150 by 2017).

And alongside all this, the Perkins will continue to rotate their own arable crop between the rows of trees, farming horizontally while the tree crop licensees farm it vertically to maximise space available for crop production (a ‘silvoarable’ agroforestry system).

It’s flipping exciting and if you’re not going to read the details then we’d just like to thank now those people who offered so much support in pulling it together: Ella, who was a horticultural student at Schumacher College, gave her time repeatedly to help with about 15 different versions of the field layout and whom we cannot thank enough for that; Martin Crawford who was ever on hand to input some of his many years of expert knowledge; Richard Kelly of Thistledown Farm for sharing his elderflower experience with us; Tom Alcott, founder of Peppermongers, who was the first person to share in the excitement that we might, in the UK, start growing sichuan for the table on a commercial scale; Jeremy and the team at Savills Exeter because we keep asking them to do things they probably think are a bit odd but they always rise to the challenge along with the 101 versions and questions about everything.

Harriet Bell (previously food & farming manager at Dartington Hall)

[content-box title=”The long read” colour_group=”green”]

If you want the detailed version then I’ve endeavoured to organise it into the relevant sections (click to jump to content):

Which trees and why did we chose them?

The legal/management framework

[/content-box]

Why 48 acres of agroforestry?

In 2014, we were recruiting a new farm tenant for Old Parsonage Farm, which is the largest farmstead and takes up most of the farmland on the estate. Our Land Use Review project had resulted very unusually in the insistence by the Trust that whomever took on the farm deliver 48 acres of agroforestry as part of their tenancy.

There are many reasons for encouraging agroforestry, and more trees on farms generally, summarised in this video by Agricology:

[fve]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZhlP1rO0Yw[/fve]

For the Trust as the landowner, maintaining and rebuilding soils, enhancing the biodiversity of the estate and endeavouring to positively contribute to reducing the risk of localised flooding in an era of climate change are part of our role as responsible stewards of the land.

For some potential tenants however it was rather off-putting – trees are expensive, they can take years to return the initial investment of planting them, many would have seen it as a waste of a good arable field and farmers tend to specialise – horticulture or livestock for example (though this is a generalisation). Thankfully one of the reasons we felt Jon and Lynne Perkin were a great fit for Old Parsonage Farm was their general willingness to try doing things differently whilst balancing pragmatism with innovation.

The slight change from the original Land Use Review plan was that instead of Jon and Lynne paying for the trees it was decided that Dartington would – before recovering this cost from Old Parsonage Farm through an increased rent of the field when the trees started cropping and the value of the crop yield from the field increased.

Which trees and why did we chose them?

We started the process of identifying the tree crops with a brainstorm, involving those on the estate with a stake in the project, relevant experience or a potential interest in the crop. Rather than narrow the choice to an obvious candidate the meeting identified numerous potential options.

As is so often the case, it was actually thinking about finances that determined the route we selected.

We did not wish to emulate existing stewardship schemes where farmers may plant a tree crop, such as apples, for environmental benefit but not in a way which necessarily fits their farm business. We wished to be sure in advance that the crop selected would have a good market value.

We could have opted for a biomass or timber crop, but as the biomass yield would have been a comparatively minor percentage of the Trust’s biomass consumption it seemed barely worthwhile, and timber would not necessarily have returned an investment during the duration of the farm’s tenancy.

We had decided that the Trust would invest in the agroforestry field in lieu of the farm because the farm was investing so heavily in starting its dairy business. In fact the Trust investing in the agroforestry field was still taking budget away from getting the farm in good order because it was coming out of a four year investment in farm infrastructure that the Trust had committed to making under the terms of the new tenancy. To speak bluntly the Trust could invest either in trees or in a new roof on one of the farm buildings (some of which date from the 1930s).

As trees can produce very valuable crops (they just didn’t happen to be part of Jon and Lynne’s farm business plans) it seemed sensible to look for potential investors whose businesses were dependent on tree crops. Very quickly we found there was sufficient appetite from other businesses wanting to be involved in the project that we could actually have put a much greater acreage to agroforestry.

Luscombe Drinks were an early point of contact as they’re very local and we knew they were amenable to being approached by people with a good crop. An initial market research email in the summer of 2015 lead to a response that indicated they had a general need for more sustainable elderflower supply – and an autumnal meeting then took place between Gabriel, Luscombe’s Owner/Founder, and the Dartington team. It became clear that interest converged and this could be, if it works, a really good partnership model going forward that helps them meet the increasing demand for their products.

Marina O’Connell, of Huxhams Cross Farm was the second port of call. Having worked at Dartington in the 1980s Marina had previously established the orchard at School Farm, adjacent to the proposed new agroforestry site. Now back at the helm of her own farm enterprise, Marina had spent the majority of the intervening years developing a specialism in top-quality fruit for the consumer market. We had been having some discussions about how to balance Marina’s own orchard plans for Huxhams Cross Farm with the habitat requirements of the wild orchids present on site, and a lateral move to the agroforestry field at Old Parsonage Farm meant that not only was there more space for wild orchids but Marina could grow more trees than she had originally anticipated.

We could have filled the field with just these two participants – in fact we could have filled it about four times over just with elderflower for Luscombe – but as the impetus for the project was experimental land use then crop diversity was felt to add value and help spread risk.

Our final choice is probably the riskiest of all. Sichuan pepper has never been grown at this scale in the UK before (that we’ve been able to discover anyway). We don’t doubt that it can be as the inspiration for the plant choice came from the estate itself. Martin Crawford, of The Agroforestry Research Trust, has been growing Sichuan here for many years and has several healthy and mature trees next door to Old Parsonage Farm. If you’ve never visited either his demonstration forest garden or his trial site but you appreciate an unusual edible, then we highly recommend his tours and courses.

However, it wouldn’t have occurred to us to grow it if it hadn’t been for the Observer Food Monthly’s ‘OFM 50’ of January 2015 – a list of ‘the 50 hottest places, people and trends in food’. We were celebrating goat taking the number 1 slot, just as Old Parsonage Farm were preparing to launch their Dartington Dairy goat enterprise on the estate, when reading through the rest of the list Peppermonger’s Sichuan Pepper jumped out at number 15. Having just been on a tour of Martin Crawford’s site and tasted the amazingly impactful, tongue tingling, zesty, lip numbing pods fresh from the tree, this seemed like a sign that here could be a crop which might be for Dartington what tea has been for Tregothnan – something truly special and valuable, offering unique quality and provenance.

It wasn’t quite as simple as that though. In fact it took about nine months before the phrase ‘Sichuan pepper’ could be uttered without a number of people in the vicinity rolling their eyes and shaking their heads in incredulity.

A recent favourite phrase of mine is “there are always flamingos”. It comes from The Tree House, a book on ‘eccentric wisdom’ and how to ‘see’, and the central character is arguing for a particular discernment in relation to which details matter – that sometimes it doesn’t matter if you don’t know where your keys and your wallet are as long as you’re able to notice the flamingos in your backyard. “I think the discovery of a flamingo in your backyard is of a higher order of excitement than ‘Where the hell’s my wallet?’”

Sichuan was the flamingo in our backyard, but sometimes it’s hard to acknowledge the flamingo without worrying you’re coming across as a bit odd. But if one puts one’s farm business hat back on, if no one’s growing Sichuan then why not create a new product and have the market to yourself, even if it’s a bit more of a risk?

Thankfully another market research email, this time to Peppermongers, asking if they thought UK grown sichuan was a marketable product came back with a response entitled ‘go for it’ and found a ‘big fan of Dartington’ in Tom Alcott, Peppermongers founder, an expression of interest in the eventual crop and an offer to help out and be involved.

A combination of Tom’s expert knowledge from the market side and Martin Crawford’s expert knowledge from the growing side helped pull together the calculations around growing and management requirements and anticipated yield. Tally that against Peppermongers existing sales and generally there’s evidence for a business case for the crop. As it happens, there is also currently an import ban – so there’s no fresh Sichuan coming into the UK at the moment, meaning we could end up with the UK’s only supply. The business case eventually brought the eye rollers around to the potential.

The processing element was a bit of a weak point for everyone. Peppermongers don’t usually process their pepper directly and Martin only has a few trees of his own so we knew roughly the methodology but didn’t necessarily have the facilities for the intended scale of production. To be honest this is still the weakest link in the chain. The Sichuan pepper will require hand picking, but so will the apples and the elderflower, so this should be achievable (if a slightly thornier task and Brexit permitting a willing labour force is available). However the pepper also requires immediate dehydration and potentially dehulling which is all a bit easier in China where it can cost-effectively be done by hand. It would be a fib to say we’re certain at this moment how we’re going to process the crop but we’re feeling confident enough about it that, with five years still to figure it out from the moment we plant the trees before we have a crop worth processing, it seemed worth at least getting the trees in the ground. All that remained was for Martin to grow on for us the appropriate number and in 2016 the first 96 two-year-old trees will be ready.

Of course it’s easier to take this risk knowing that the rest of the field will be planted with crops we’re much surer of the management and market of.

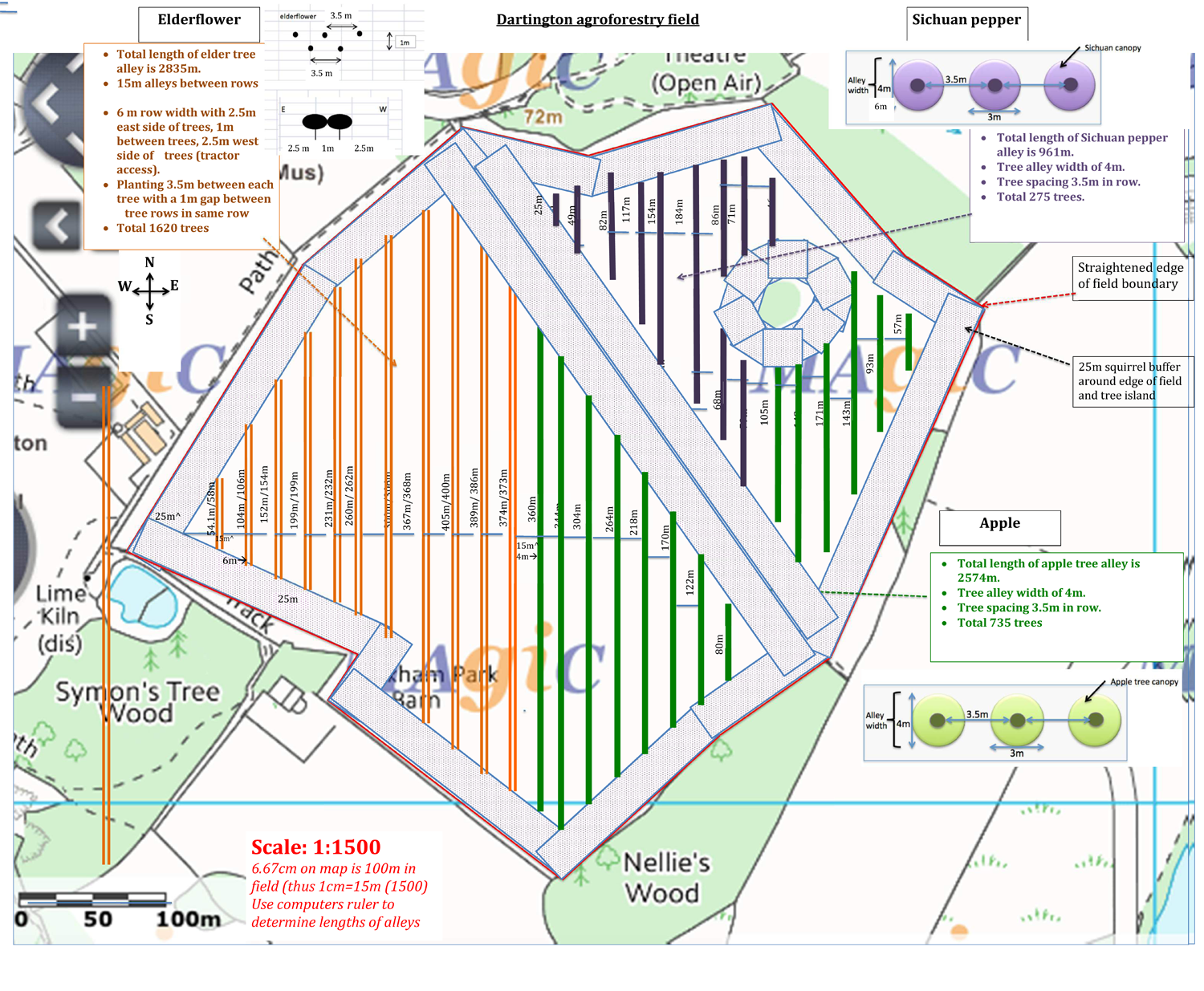

Field design

Developing the final design of the field has been a bit slow going: ask five different experts; get five different answers. But once the 2016 budgetary year for this project started we were able to bring in Stephen Briggs, a farmer experienced in silvoarable, to expedite things by telling us what to do.

The telling to the mapping out has still taken more than a dozen drafts as people have changed their minds about their requirements, realized which details we’d neglected (tractor turning circles adjacent to the footpath), endeavoured to incorporate different preferences of plants and people, factored in the impact on the visual aesthetic of the Dartington gardens and endeavoured to maximize all potential benefit from the field.

Trying to spend as little money as possible and not having a particularly workable mapping tool, mapping the field out was a process rescued by Ella, a horticultural student at Schumacher College with an enthusiasm for agroforestry, the ability to make Defra’s MAGIC map and Microsoft Word talk to each other, and the patience of a saint.

Establishing whether the final design is as optimal/workable as we hope or whether it is overly compromised/complicated will be a most valuable learning going forward.

The legal/management framework

One of the issues which added extra complication both for the layout and the legal arrangements between parties was endeavouring to factor in stewardship payments and subsidies with an additional view to maximizing them under potential future agri-environment schemes if at all possible.

The easiest option would have been if The Dartington Hall Trust, as the land owner, could have made an exemption and permitted the tenants of Old Parsonage Farm to sublet the trees to all the parties involved on a 15 year Farm Business Tenancy (FBT). However, the farm receives Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 support for the land within its tenancy under the Common Agricultural Policy. If the land were to be let on separate FBT’s there was potential for the sub tenants to be ineligible for Pillar 1 support as they would have been under the minimum claim area (minimum 5 hectares required).

Having said that, whether or not the field will be able to retain all payments is still under question as the UK government opted not to support agroforestry when it designed the latest Countryside Stewardship Scheme (something Dartington and many others feel was an error), although they have recently announced some changes – and the rules on trees in fields are open to interpretation.

With regards to BPS Trees are eligible if they (this is BPS):

…are scattered within an agricultural parcel (each tree is surrounded by agricultural land), and

…allow agricultural activity to be carried out in the same way as in parcels without trees in them.

So the case is there for the arguing.

Either way it was decided the best way to proceed would be through granting a licence for the tree strips instead of an FBT, with Jon and Lynne Perkin of Old Parsonage Farm remaining in management control of the land upon which the trees are planted for the purposes of Stewardship and in occupation and farming the land for the purposes of BPS. However, this solution brought up a new set of problems. If you’re going to invest in trees from which you won’t see a return on your investment for some time then you’re unlikely to do this without feeling secure in being able to use the piece of land on which they’re planted for a sufficient period to see a return on one’s investment

Whilst some participants were amenable to entering into a license in good faith, proceeding on such grounds would of course make participation a greater financial risk. Thankfully a simple solution presented itself in that, whilst the licence agreement was between those planting the trees and the farm tenant who rented the field, Dartington Hall Trust could, as the land owner, provide a separate undertaking to ensure the continuation of the licence on the same terms regardless of who was the tenant at Old Parsonage Farm – thus securing the participants licence to use the land upon which the trees were planted even if the tenancy of the farm changes.

Getting further into the nitty gritty were the details around the organic status of the field and future crops. Old Parsonage Farm is currently managed organically under the terms of the FBT but not certified as organic by an outside body (such as the Soil Association or Organic Farmers & Growers). Every licensee responsible for a tree crop wanted the field to be certified as organic. For Marina there is no business case for her apples if they’re not certified organic – the value for a non-organic apples are simply not high enough to justify planting and harvesting the trees.

Luscombe ‘will put only the best in the bottle’ using either organic or wild ingredients. As this is their first batch of cultivated (rather than wild hedgerow) elderflower it is important to their business ethos that it can be certified as organic. And whilst certified organic Sichuan is not that common, it was felt that certification would further distinguish the provenance and quality of this pepper from other sources. So, the farm is already farmed organically, everybody wants it to be certified – what’s the issue?

Old Parsonage Farm is currently in a Higher Level Stewardship Scheme (or HLS, part of Pillar 2 of the Common Agricultural Policy). This means it receives funding for activities which have a wider environmental and social benefit than just for the farm itself – for example planting and restoring hedgerows to support the nation’s birds. The farm was entered into the scheme under the previous farm tenant who was not organic, which means that the current tenant gets no support for transitioning the farm into organic management despite seeing a loss in farm productivity as a result.

It can take some years for the natural fertility to recover during the organic conversion process, which is why farmers often rely on organic conversion payments to help them through this time of transition. Currently Old Parsonage Farm are going cold turkey but they really would like some financial help as they are seeing an immediate decline in yield. So the plan already in place was to wait until the December 2018 break clause in the HLS and then put the farm into the new Countryside Stewardship Scheme with organic conversion support – but we wouldn’t be able to do this until January 2019.

So whilst the farm tenants wished to delay starting conversion until January 2019, the preference for some was for organic conversion at the earliest possible opportunity – not least because it takes three years to convert a tree. A brief discussion with the Soil Association’s Certification team suggested that the field could be put into certification separately from the rest of the farm holding, as it was not being utilized for the farm’s core purpose.

In the end though, our tree licensees compromised and deferred to best interests of the farm tenant, as none of the trees will crop at a truly productive level until about year five, making achieving organic certification for the whole field by 2022 seem acceptable. The inspectors for Huxhams Cross Farm agreed to extend the certification from that farmstead to the tree strips managed under the same regime on the Old Parsonage Farm.

Then of course Brexit happened – and the whole debate may prove pointless, as the continuation of farm support is now only guaranteed to 2020. It may be that waiting to 2019 to go into official conversion becomes redundant, as it may not be possible to enter the Countryside Stewardship Scheme in its last guaranteed year of existence – and the future of continued financial support for the UK’s farmers is deeply uncertain.

So it wasn’t until the beginning of September this year that we had a workable version of the license ready – but not yet signed – and it’s amazing how reaching a point of actually being expected to sign a contract finely tunes everyone’s critical eye that little bit more.

Ultimately what we have endeavoured to do, and what has taken so long, is to create a document which balances everyone’s needs as equitably as possible, incentivises cooperation and mutual benefit and dissuades stakeholders from taking actions that lack consideration for one’s fellow field occupants.

Planting should start from January 3, 2017.

I feel more informed. Thanks Harriet. Great project.

Good luck with this The Sechuan pepper is a great idea. A few years ago I made a film called ‘A Forest Garden Year’. It followed Martin Crawford’s garden on the Estate throughout the seasons, and is a practical guide to forest gardening. If anyone is interested it’s still available from Green Books.

Thanks for your vote of confidence Malcolm 🙂

Wow, what a tangled web! But you seem to have managed it all beautifully. Kudos!

Very impressed you made it to the end of the blog Tara and thank you, though we’re not quite there yet, still got to get the trees in the ground 🙂